Behavioral Economics and Investing

Behavioral Economics studies and describes economic decision-making. According to its theories, actual human behavior is less rational, stable, and selfish than traditional normative economic theory suggest.

This topic is extremely important for investors as it helps explain why we humans are subject to errors in our decision making that usually lead to poor financial outcomes.

At Dynic Wealth Management we acknowledge that behavioral biases are inevitable for everyone. The crucial aspect is recognizing when these biases are affecting our judgement. Our role is to serve as coaches for our clients, offering objectivity and guidance during periods of heightened stress when investors are most susceptible to making errors.

The Core of Behavioral Economics

Heuristics

Heuristics are commonly defined as cognitive shortcuts or rules of thumb that simplify decisions, especially under conditions of uncertainty. They represent a process of substituting a difficult question with an easier one (Kahneman, 2003). Heuristics often lead to Cognitive Biases.

Cognitive Bias

A cognitive bias is a systematic error in thinking, in the sense that a judgement deviates from what would be considered desirable from the perspective of accepted norms or correct in terms of formal logic.

Bounded Rationality

Bounded Rationality states that humans are not rational 100% of the time because there are limits to our thinking capacity, available information, and time (Simon, 1982). This is why biases and mistakes often occur.

Dual-System Theory (Thinking, Fast and Slow)

Dual-system models of the human mind contrast automatic, fast, and non-conscious (System 1) with controlled, slow, and conscious (System 2) thinking (see Strack & Deutsch, 2015, for an extensive review). Many heuristics and cognitive biases studied by behavioral economists are the result of intuitions, impressions, or automatic thoughts generated by System 1 (Kahneman, 2011). Factors that make System 1’s processes more dominant in decision making include cognitive busyness, distraction, time pressure, and positive mood, while System 2’s processes tend to be enhanced when the decision involves an important object, has heightened personal relevance, and when the decision maker is held accountable by others (Samson & Voyer, 2012; Samson & Voyer, 2014).

Put another way, the Dual-System Theory says humans have 2 systems of thinking--System 1 is unconscious, quick, and makes use of shortcuts whereas System 2 is intentional, calculated, and often more accurate, but takes more time and effort. Due to the amount of information we take in on a daily basis we humans rely mostly on System 1 when making decisions, but the sloppiness of this system's process is where many mistakes are made.

Common Biases and Heuristics

Overconfidence

The Overconfidence Effect is observed when people's subjective confidence in their own ability is greater than their objectual (actual) performance. Overconfidence is often associated with excessive risk-taking (e.g. Hirshleifer & Luo, 2001), concentrated portfolios (e.g. Odean, 1998), and overtrading (e.g. Grinblatt & Keloharju, 2009).

This bias often stems from an individual's illusion of control, which involves a tendency to overestimate one's management of random events. The fact is that the future is always uncertain, so any belief that an event has 100% probability of happening is dangerous to investing--applying a range of probabilities for various events is preferred to this view. See our Thinking in Probabilities, Not Certainties page.

Overestimating one's own ability with investing can be one of the most dangerous biases for investors; it's often seen when investors take credit for things that go right but defer responsibility for things that go wrong (often blaming the market or some other cause).

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias (Wason, 1960) occurs when people seek out or evaluate information in a way that fits with their existing thinking and preconceptions. Investors often fall prey to confirmation bias when they favor information that supports their preconveived notions about an investment's potential while ignoring contradictory evidence.

The Gamblers Fallacy

The Gambler's Fallacy refers to the mistaken belief that independent events are interrelated. Investors influenced by the gambler's fallacy might erroneously believe that a stock's recent performance has some bearing on its future potential.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight Bias happens when being given new information changes our recollection from an original thought to something different (Mazzoni & Vannucci, 2007). This bias can lead to distorted judgements about the probability of an event's occurrence, because the outcome of an event is perceived as if it had been predictable. It may also lead to distorted memory for judgements of factual knowledge. The old saying is 'Hindsight is 20/20'.

Investors exibiting hindsight bias often believe, after an event has occured, that they had accurately predicted its outcome, leading to overconfidence in their future investment decisions.

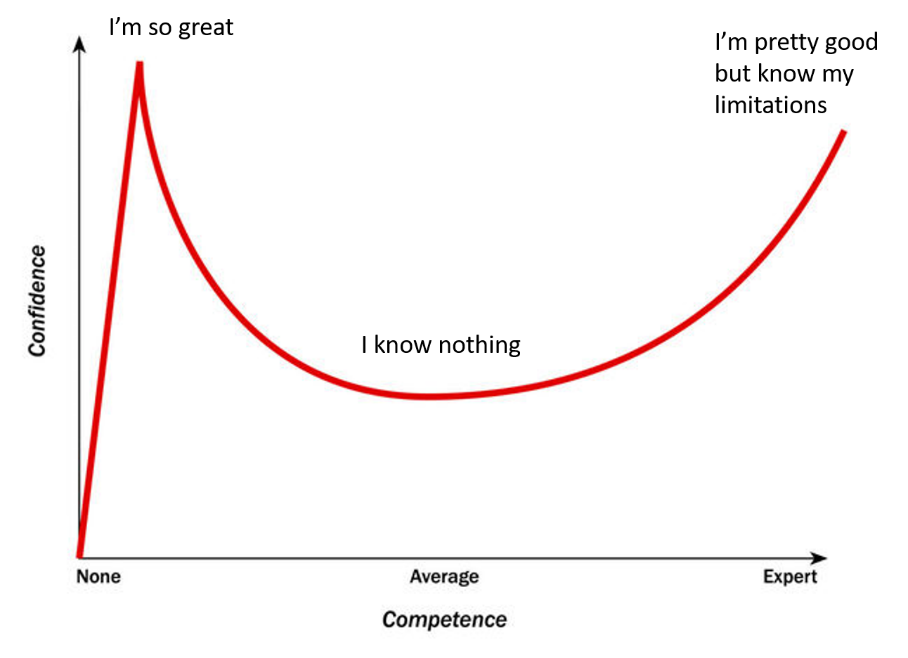

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger Efffect is a cognitive bias in which people wrongly overestimate their knowledge or ability in a specific area. This tends to occur because a lack of self-awareness prevents them from accurately assessing their own skill (Dunning & Kruger, 1999). Those with limited knowledge often suffer what Dunning and Kruger call the "dual burden" whereby people not only reach mistaken conclusions leading to regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it--people don't know what they don't know.

This bias goes hand-in-hand with Overconfidence and aligns with the old saying "knowing enough to be dangerous." Novice investors often fall prey to Dunning-Kruger when the investment landscape changes and what used to work no longer works.

Loss Aversion

Loss Aversion is encapsulated by the expression "losses loom larger than gains" (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979a). It is thought that the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. People are more willing to take risks (or behave dishonestly, e.g. Schindler & Pfattheicher, 2016) to avoid a loss than to make a gain.

This is especially relevant for investors as humans tend to experience twice as powerful a negative emotion for an investment loss than they would for the same sized investment gain.

Loss Aversion may cause an investor to hold on to a declining investment for too long, hoping it will rebound to avoid realizing a loss. This behavior can result in missing out on other potentially profitable investments and ultimately lead to a larger loss if the investment continues to decline. Many other biases and heuristics result from the dispraportionate emotional effects of losses vs. gains.

Myopic Loss Aversion

Myopic Loss Aversion occurs when investors take a view of their investments that is strongly focused on the short term, leading them to react too negatively to recent losses, which may be at the expense of long-term benefits (Thaler et al., 1997).

Ambiguity (uncertainty) Aversion

Ambiguity Aversion is the tendency to favor the known over the unknown, including known risks over unknown risks.

Action Bias

The action bias occurs when people have an impulse to act in order to gain a sense of control over a situation and eliminate a problem. Investors influenced by action bias might feel compelled to make frequent trades or changes to their portfolio, believing they must constantly take action to achieve better results. This bias is opposite the Status Quo Bias.

The Action Bias may be more likely among overconfident individuals or if a person has experienced prior negative outcomes (Zeelenbert et al., 2002), where subsequent inaction would be a failure to do something to improve the situation.

Herd Behavior

This effect is evident when people do what others are doing instead of using their own information or making independent decisions. Herding behavior can be increased by various factors, such as fear (e.g. Economou et al., 2018), uncertainty (e.g. Lin, 2018), or a shared identity of decision makers (e.g. Berger et al., 2018).

Herd Behavior is particularly evident in the domain of finance, where it has been discussed in relation to the collective irrationality of investors, including stock market bubbles (Banerjee, 1992).

Fear of Missing Out

FoMO refers to "a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent" (Przybylski et al., 2013). People suffering from FoMO have a strong desire to stay continually informed about what others are doing.

FoMO often leads investors to chase performance.

Recency Bias

The tendency to place too much emphasis on experiences that are freshest in our memories--even if they aren't the most relevant or reliable.

Present Bias

The Present Bias refers to the tendency of people to give stronger weight to payoffs that are closer to the present time when considering trade-offs between two future moments (O'Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). This bias is more often used to describe impatience or immediate gratification in decision-making.

This bias is often cited as a reason for low retirement savings rates as people tend to be present-biased, often delaying tasks that do not offer an immediate reward (Schouwenburg & Groenewoud, 2001). The further away the event, the less effect it has on us today.

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring happens when initial exposure to a number serves as a reference point and influences subsequent judgements. The process usually occurs without our awareness (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

This is often seen when investors focus solely on the value of their portfolio as of the latest statement, looking at performance relative to that value. This can lead to various action-related biased decisions.

Status Quo Bias (Inertia)

The Status Quo Bias is evident when people prefer things to stay the same by doing nothing or by sticking with a decision made previously (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988). This may happen even when only small transition costs are involved and the importance of the decision is great.

Investors exhibiting status quo bias often prefer to stick with their current investments, even when better opportunities are available, due to a reluctance to change. The Status Quo bias is the opposite of the Action Bias.

Endowment Effect

This bias occurs when we overvalue a good that we own, regardless of its objective market value (Kahneman et al., 1991).

The Endowment Effect is evident when investors become reluctant to part with a stock they own in exchange for its cash equivalent, or if the amount that they are willing to pay for the stock is lower than what they are willing to accept when selling the stock.

IKEA Effect

The IKEA effect is evident when invested labor leads to inflated product valuation (Norton et al., 2012).

DIY'ers are susceptible to this as they place higher value on the things they laboriously created.

Choice Overload

Choice Overload occurs as a result of too many choices being available to consumers. Commonly referred to as Analysis Paralysis, investors often choose the status quo instead of making a necessary change when overwhelmed with options. Choice Overload can be counteracted by simplifying choice attributes or the number of available options (Johnson et al., 2012). The Framing Effect plays a large role in choice overload.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

Individuals commit the sunk cost fallacy when they continue a behavior or endeavor as a result of previously invested resources (time, money, or effort) (Arkes & Blumer, 1985).

This often comes about when investors are reluctant to sell an investment at a loss believing that if they sell then the loss becomes real instead of viewing the prospects for said investment relative to other opportunities available to the investor.

Information Avoidance

Information Avoidance refers to situations in which people choose not to obtain knowledge that is freely available (Golman et al., 2017). Information Avoidance usually has immediate hedonic benefits for people if it prevents the negative (usually psychological) consequence of knowing the information, but it usually carries negative utility in the long term because it deprives people of potentially useful information for decision making and feedback for future behavior.

In finance, investors are often less likely to check their portfolio online when the stock market is down than when it is up (Karlsson et al., 2009).

Rational Ignorance

When information is long or presented in a cumbersome fashion, it may lead consumers to consider the time costs of reading it greater than the benefits of being better informed, thereby encouraging them to make a less informed decision (Downs, 1957).

Representative Heuristic

Representative Heuristic is used when we judge the probability that an object or event A belongs to class B by looking at the degree to which A resembles B. When we do this, we neglect information about the general probability of B occurring (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972). Representativeness-based evaluations are a common cognitive shortcut across contexts that create issues when prior probabilities (base rates) are ignored.

Investors may prefer to buy a stock that had abnormally high recent returns or misattribute a company's positive characteristics (e.d. high quality goods) as an indicator of a good investment (Chen et al., 2007). This tends to lead investors to 'chase performance' which is a common mistake. Investors also fall victim to this heuristic when judging an invesment's future performance based on its similarity to past successful invesetments, rather than on thorough analysis.

Availability Heuristic

Availability Heuristic is when people make judgements about the likelihood of an event based on how easily an example, instance, or case comes to mind.

For example, investors may judge the quality of an investment based on information that was recently in the news, ignoring other relevant facts (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

Framing Effect

Choices can be presented in a way that highlights the positive or negative aspects of the same decision, leading to changes in their relative attractiveness.

Mental Accounting

Mental Accounting says that people treat money differently, depending on factors such as the money's origin and intended use, rather than thinking of it in terms of the "bottom line" as in formal accounting (Thaler, 1999). Treating fungible assets differently can lead investors to lose out on the bigger picture of the portfolio.

Investors affected by mental accounting may irrationally separate their money into different accounts or categories, treating it differently depending on its source or intended use, rather than viewing it as a single, fungible resource. For example, an investor may treat gains in account differently than contributions, viewing the gains more like 'house money' that can be used for riskier investments.

Money Illusion

The tendency for people to think of monetary values in nominal rather than real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

Cognitive Dissonance

The uncomfortable tension that can exist between two simultaneous and conflicting ideas or feelings often as a person realizes that he/she has engaged in a behavior inconsistent with the type of person he/she would like to be or be seen publicly to be. People are motivated to reduce this tension by changing their attitudes, beliefs, or actions. Rationalization/Justification is often used as methods to overcome this feeling of tension.

This shows up when investors know staying invested is the most objectively sound decision, yet sell anyways and come up with a justification for the decision to put their mind at peace. Alternatively, they may also hold on to a losing investment because they convinced themselves that the situation will improve, despite conflicting evidence suggesting they should sell.

Source: Samson, A. (Ed.)(2022). The Behavioral Economics Guide 2022. https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/be-guide/.